⚖️ The rate-length law of protein folding

Published:

In 1969, Levinthal proposed a famous paradox, which pinpoints why protein folding – that is, the ability of proteins to find a single native state conformation in which their free energy is minimized – is so remarkable.

Levinthal asked us to consider a rather small protein, only 100 amino acids long. Suppose for a moment that each amino acid can adopt at least 3 discrete conformations, independent of the configuration of any other residue. That’s a gross approximation, but certainly an underestimate of the total possible ways a protein can wrap and wriggle its atoms. But the result is a huge number of possible configurations for the entire protein chain, \(3^{100}\) or on the order of \(10^{47}\). Even if the protein were to sample these conformations extremely quickly, say 1 per picosecond, the time it would take to perform an exhaustive search would be ~\(10^{28}\) years. To put that in some kind of perspective, a picosecond is very fast; light only travels about a foot in a picosecond. And \(10^{28}\) years is very, very, very slow; we know the universe is about \(10^{10}\) years old!

Instead, proteins – even much larger proteins – fold quite quickly, typically in milliseconds to seconds. The obvious conclusion is that during folding, proteins don’t search all possible conformations. That would simply take too long. They must have some kind of guiding force pushing them towards the correct solution, the native state. An equivalent way to say this, using different language, is that protein energy landscapes are “funneled”. The funnel simply states there’s on average a net force towards the native state. It follows logically from Levinthal’s paradox.

Over the years, there has been a lot of work put into trying to understand how this net force arises from the microscopic interactions that hold proteins together. It would be great to have a simple theory about what kinds of systems exhibit self-assembly to a single native state in reasonable timescales, but while we understand a lot, I would argue such theories have remained elusive so far.

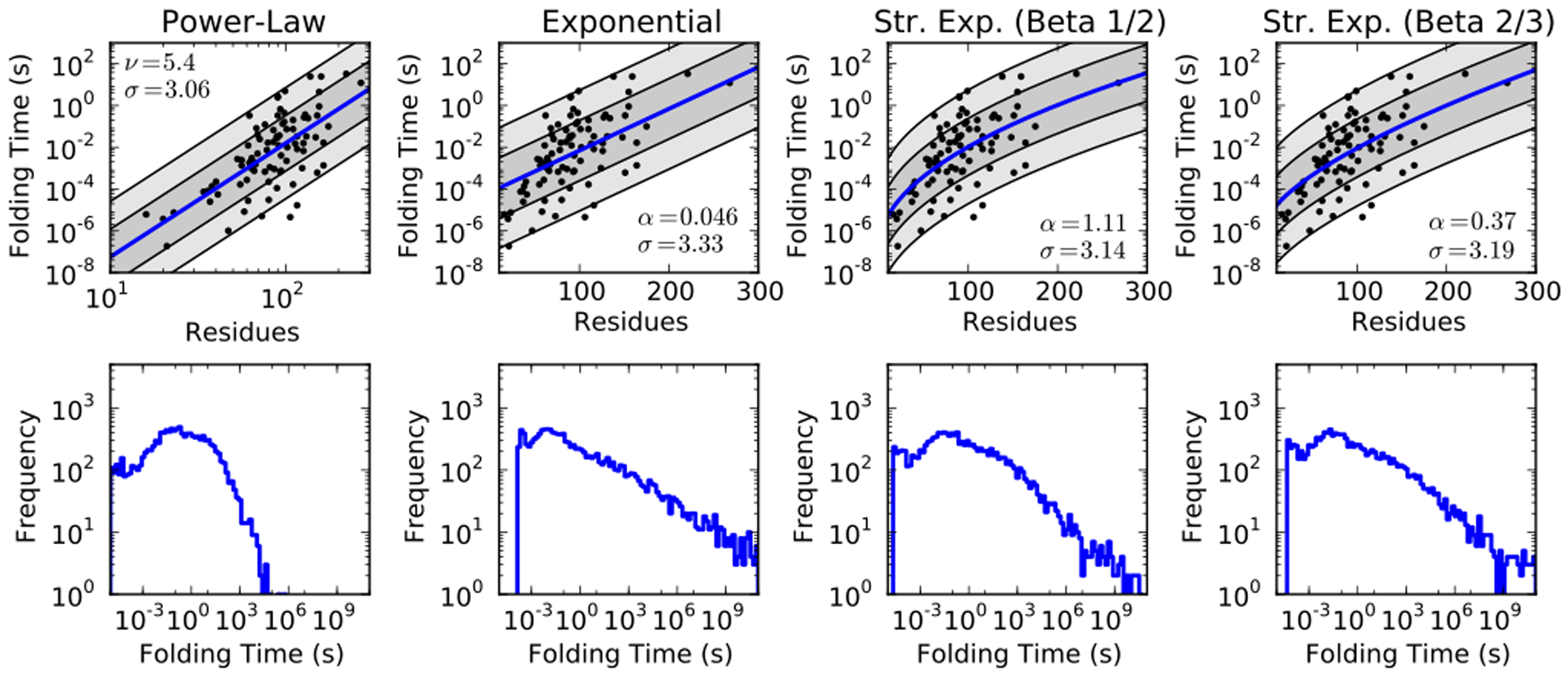

One way to highlight this gap in our understanding is our failure to definitively agree on what I call the rate-length law of folding. The idea is simple: as proteins get longer, how does the average folding time change? For instance, the time may grow exponentially with protein length (\(\tau \sim e^{N}\)), or as some unknown polynomial (\(\tau \sim N^{\alpha}\)), or perhaps a stretched exponential (\(\tau \sim e^{N^{\beta}}\)). Different theories have predicted different rate-length laws, so this is an experimentally testable relationship that can falsify models.

Using published protein folding studies, we can see how different rate-length laws stack up against the data:

Unfortunately, while we can say for certain that proteins fold more slowly as they get larger, too few proteins have been measured to definitively determine how much slower they get. More data would help. The experiments require the measurement of the folding times of many proteins; straightforward, but labor intensive. My hope is that automation and renewed interest in this topic will help bridge this experimental gap.

Computer scientists may have already noticed that the rate-length law is interesting for another reason. In a deep way, it’s asking what the computational complexity of the folding search algorithm is: exponential or polynomial? Since we expect the free energy landscape of protein conformational space to be non-convex, with no other knowledge about its structure, the search for a free energy minimum is expected to require a brute-force approach. Since, according to Levinthal-like arguments, the conformational space grows exponentially with protein length, we therefore expect the rate-length law to be exponential. For you non-computer science folks, exponential means slow!

A sub-exponential folding “algorithm”, breaking this simple logic, would therefore provide a very powerful answer to Levinthal’s paradox. It would also be an extremely interesting and surprising statement about the physics of polypeptide chains, or perhaps which sequences evolution selects to enable folding.

My personal opinion, however, is that the rate-length law is very likely exponential. It’s the most prosaic answer. It would explain why we don’t observe protein domains larger than ~500 amino acids in nature, and that protein complexes larger than this are made up of many individual domains or proteins that assemble themselves after folding into discrete units.

That said, without definitive experimental data the jury is still out, waiting for a talented experimentalist to finally determine the protein folding rate-length law!