👻 Ghost Imaging

Published:

What the heck is ghost imaging? No, we’re not actually talking about taking pictures of ghosts (which was quite popular back in the day), but about a certain philosophy of measurement. The back-story and namesake of the technique start with a certain class of experiments looking into quantum entanglement. Folks were trying to figure out more about what Einstein famously called “spooky action at a distance“, where entangled particles seem to be able to share information, despite being spatially separated.

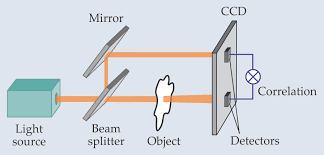

The Ghost Imaging experiment looked something like this:

Pairs of entangled photons are generated, typically by a process known as “parametric downconversion”. One photon from each pair is sent into an object, and a “bucket” detector records if it makes it through or is absorbed. The other photon is sent straight to a 2D imaging detector, where it’s spatial position is recorded. Surprisingly, if we correlate the bucket at 2D signals, the resulting correlation is an image of the object – even though we never resolved any spatial information from the photons that interacted with the object! The photons must be sharing information!

Perhaps unfortunately for ghost fans, the explanation is fairly simple. The entangled photons are both generated from a single, upstream photon, and therefore they must conserve both energy and momentum. The momentum conservation means the direction they travel is correlated… regardless of any quantum effects. Basically what is happening is the following: the photon that hits the area detector just tells us what direction both photons are traveling. Then the bucket detector tells us how “dark” the object is in that direction. Repeat the measurement many times, and you can probably see how ghost imaging works. There are deep and clear connections to the single-pixel camera, multiplexing methods such as FTIR, and linear regression.

That doesn’t mean it’s not interesting. What we’ve done is taken a random source – photons from parametric downconversion – and then instead of trying to control the light, we simply measure the random effects and then compute the result we would have had, should we have had control. Often, measurement is cheaper, easier, or possible in cases when control isn’t, so we can turn this to our advantage!

When I personally realized this, I was working at the LCLS free electron laser (FEL), and my friend Daniel Ratner had been slaving away trying to come up with ways to control the FEL via a process known as seeding. We realized we could actually forget about all about the tricky process of control, and use our existing diagnostics to obtain the same information! This could be done in space, as in the classic ghost imaging experiment, but also in the time or energy domains. James Cryan coined the latter, a replacement for traditional spectroscopy, “spooktroscopy“, and thereby claimed the title of nameking. He also published a few excellent papers on the topic.

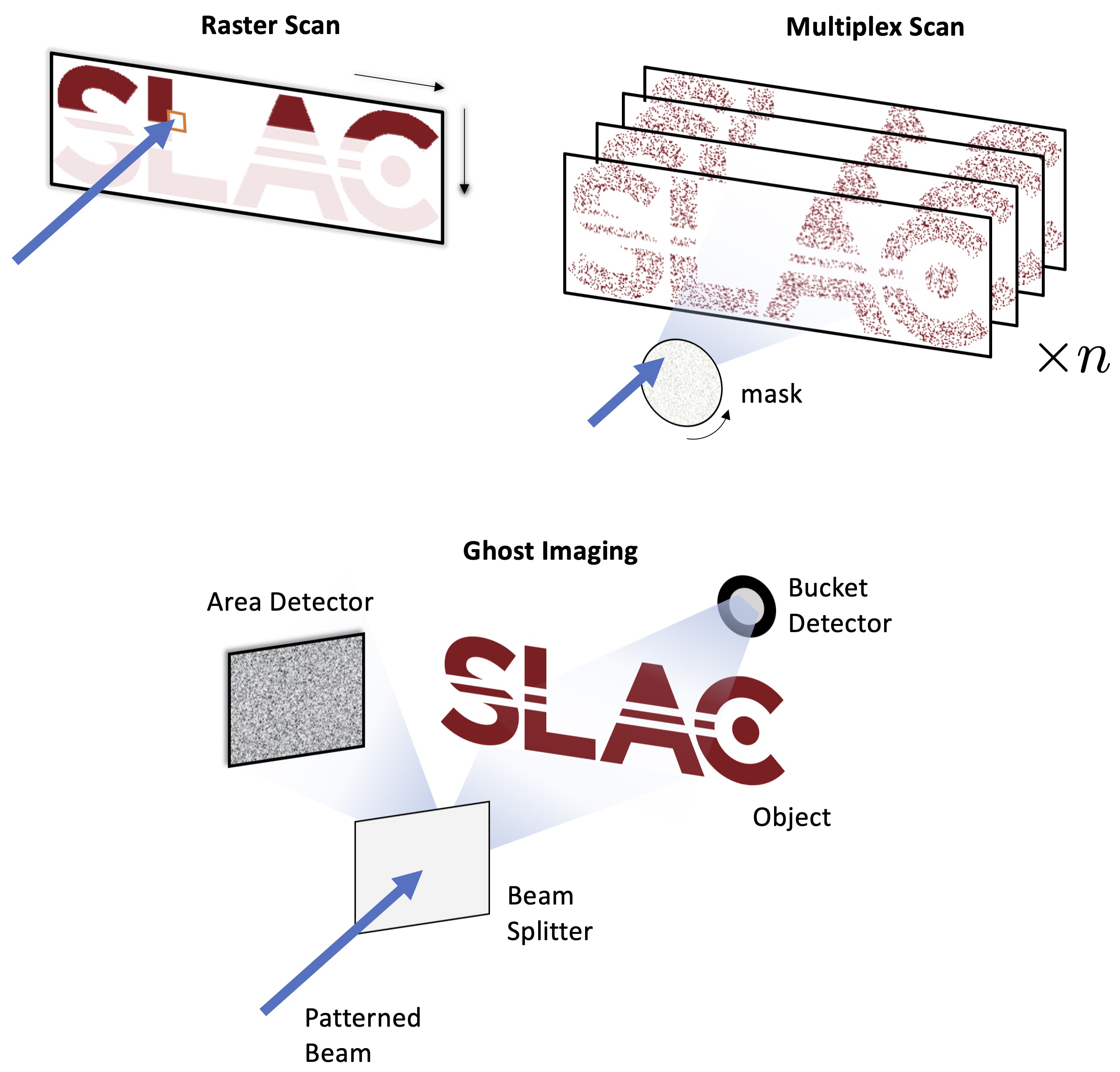

So, should you try ghost imaging? We wrote a paper that simply used classic results in linear regression to answer this question in a general case, and weigh the merits of raster scanning, multiplexing, and ghost imaging – illustrated below – for your application.

If you’re curious to read more, and have an interest in x-rays in particular, I recommend you check out the work of David Paganin and his colleagues. There are many bright people working in the field, too many to list here, so I’ll apologize to my colleagues for the short list of shout-outs and ask folks to refer to papers on the subject for a more in-depth literature list.