💦 Could there be two types of liquid water?

Published:

You probably think of water as the most important liquid in your life. It also happens to be one of the strangest and most interesting substances we know about.

Water’s properties are best described as anomalous, meaning that various measurements of water produce the opposite result from what we might expect. Water’s most famous anomalous property is its density maximum at 4°C. As the temperature decreases and the thermal kinetic energy in a liquid is reduced, most liquids do exactly what you might guess: they contract slightly, occupying less space per molecule. Water follows this pattern… until, mysteriously, at 4°C, it reverses course, and the molecules start to separate again, causing the density (mass per unit volume) to decrease!

Other anomalies abound. For example, water’s compressibility drops as temperature increases until about 46.5°C, but below that point, it becomes easier to compress as the temperature decreases further. Increased pressure shifts the melting point of water to colder, not warmer, temperatures. Finally – and of note for later in this post – water can form two different glasses, a high-density amorphous (HDA) form and a low-density amorphous (LDA) form, each with a distinct molecular structure. Martin Chaplin has categorized and described the known anomalous properties of water in an impressive list.

Ultimately, water’s strange properties result from tension built into the molecule itself. Of the six outer-shell electrons in water’s oxygen, only two are involved in forming covalent bonds with hydrogen atoms, leaving four electrons in non-bonding pairs. These two electron pairs, repelling one another, position themselves as far apart as possible. Such an arrangement would typically result in a tetrahedral shape, with an ideal bond angle of 109.5° between the lone pairs and O-H bonds. However, because the two non-bonding pairs have an equilibrium position closer to the oxygen nucleus, they exert a greater average force on the bonding electrons, pushing the hydrogen atoms closer together. This leads to a distorted tetrahedral shape, with the H-O-H bond angle reduced to 104.5°. Deviation from perfect tetrahedral geometry frustrates water’s attempts to simultaneously satisfy hydrogen bonding between all molecules in a tetrahedral lattice, generating the molecular-scale complexities reflected in water’s properties.

But the macroscopic (thermodynamic) consequences of this microscopic frustration are hard to reason about, requiring phenomenological models to explain the anomalous properties of bulk water. One of the most interesting proposals that nicely explains many of water’s properties is a bit wacky: that water is not a single liquid, but two. This model proposes that the water at ambient conditions we know and love is simply a well-mixed version of these two types of liquid water, which would separate into two distinct phases if cooled sufficiently. This hypothesis stems directly from the fact that if you rapidly freeze water, you can trap it in those two different glassy states – HDA and LDA. The proposed forms of water are therefore named HDL and LDL, for high- and low-density liquids, respectively. The idea is that in its HDL form, water’s molecules fit together more tightly, sitting near their ideal van der Waals packing. In LDL, water molecules could spread further apart, enabling a greater number of hydrogen bonds to be satisfied. High pressures would favor HDL, which has a higher density, while lower pressures would promote LDL.

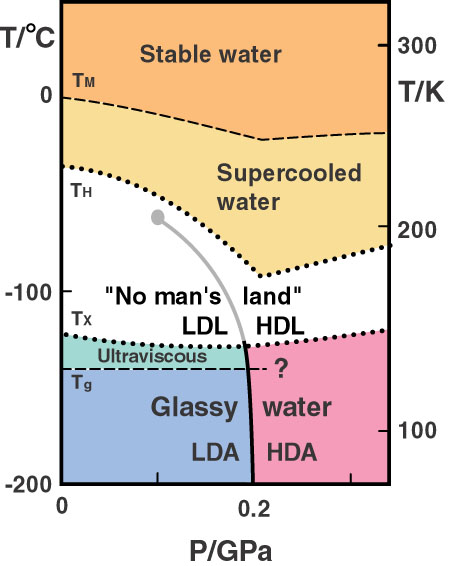

This model requires that HDL and LDL should, under specific conditions, phase separate into two distinct forms of liquid water. Therefore, it should be possible to experimentally validate or falsify this model by probing the structure of liquid water as it crosses this clearly defined boundary. The only problem: the phase coexistence line is expected to appear around 200 K and below, as illustrated in the phase diagram below:

At these temperatures, liquid water spontaneously and rapidly undergoes homogeneous nucleation – that is, it freezes and forms ice! As a result, the phase coexistence line is said to lie deep in “no man’s land,” a region of pressure-temperature space that’s notoriously hard to probe experimentally.

The XSoLaS team led by Anders Nilsson of Stockholm University has pioneered beautiful experiments using the ultrafast light provided by XFELs to open up no man’s land and reveal its secrets. While at the LCLS, and then on sabbatical in Stockholm in 2019, I was able to participate in a number of experiments with Anders’ team. Using evaporative cooling and laser-based flash heating, they have found evidence of a phase transition in liquid water by probing no man’s land from both above (cooling) and below (heating). For instance, in one of our most exciting experiments together, we traveled to PAL-XFEL in Korea, and by heating amorphous water glasses, found the signatures of two distinct forms of liquid water using wide-angle x-ray scattering. The evidence for two forms of liquid water is growing!

Lars Pettersson, who leads the theoretical component of XSoLaS, likes to say: water isn’t one complex liquid, but two simple liquids with a complex relationship. A beautiful way to stay something totally crazy.