🧬 How does photolyase repair DNA?

Published:

Anyone who’s suffered a sunburn knows first-hand that the sun can be harmful. Discomfort isn’t the only reason to take shelter in the summer, though. Direct sunlight can wreak havoc on cells’ DNA, causing up to 100 DNA damage events per exposed cell each second! In the worst case, this damage leads to dangerous cancers. To cope, humans and all other species employ DNA repair enzymes that are constantly working to keep our genomes healthy.

One especially powerful DNA repair enzyme is photolyase. Photolyase is special because it uses the energy of sunlight to repair DNA damage caused by the sun. Photolyase repairs the most common forms of sunlight-induced damage, where two pieces of DNA become incorrectly chemically bonded to one another after absorbing UV radiation.

Unfortunately, we humans suffer more from this UV damage than most other organisms because, while nearly all life on Earth can use photolyase to fix their own DNA, we lost this ability some time ago during our evolutionary history. We think this happened when our ancestors were nocturnal and didn’t need to worry about the sun as they went about their nighttime rituals. If you look around on a sunny day, photolyase is repairing DNA in the plants, animals, and microbes all around you.

Recently, my team published a paper describing the intricate details of how photolyase works. We were interested in understanding how photolyase works and focused on three questions. First, we knew the enzyme absorbed light from the sun, then used the energy in that light to drive DNA repair. In between these two steps, the enzyme has to hold onto the light’s energy in the form of an unstable “excited state” long enough to conduct the repair chemistry. We knew photolyase must use a clever system to not lose that valuable energy before it could be put to use, and wanted to understand how that process works.

Second, we wanted to know more about the DNA repair reaction itself. The damaged DNA has two chemical bonds that shouldn’t be there, caused by UV radiation. We knew photolyase breaks both bonds, but for decades scientists debated whether these two bonds break simultaneously or one at a time.

Finally, when photolyase discovers a piece of damaged DNA, it grabs it, then waits until it absorbs enough sunlight to repair the damage. Once this job is done, it quickly releases the repaired DNA and goes looking for another bit of damage to repair. We wanted to know how, exactly, photolyase distinguishes between damaged and healthy DNA.

To answer these three questions, our team decided to make a movie of photolyase performing DNA repair. This isn’t easy. First, photolyase is small: we needed to be able to resolve individual atoms to answer these questions. The entire process is complete within 100 microseconds, 10,000 times faster than the blink of an eye. To capture the fastest steps, we’d have to be much faster yet. The fastest timescale we studied was 3 picoseconds, 3 millionths of a millionth of a second. Traveling at the speed of light, you’d only make it one millimeter in 3 picoseconds!

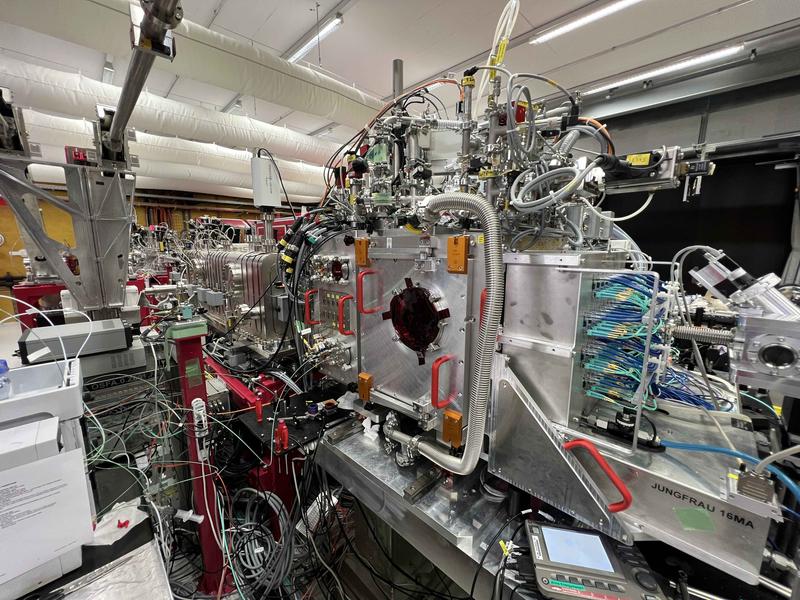

To meet these challenges, we traveled to the Swiss Free Electron Laser in Villigen, about halfway between Zürich and Basel. This facility is a 740-meter-long light source that delivers ultrafast, ultrabright pulses of X-rays, making it possible to film very small things with fast enough to catch chemistry in action. In Villigen, we used a laser flash to simulate the sun and start the repair reaction. After this, by taking snapshot “pictures” with the X-rays, we were able to make a movie of photolyase repairing DNA.

What did we find? First, that right after photolyase absorbs light, it traps this energy using an ingenious network of interactions, including two water molecules that can toggle into a new arrangement within 3 picoseconds. Second, we were able to – for the first time – confirm that the two incorrect bonds are repaired one at a time, and not simultaneously. Finally, we saw that after these bonds are broken, the repaired DNA rearranges. This causes it to take up more room, and forces it to detach from photolyase, which is then ready for another repair reaction.

Thanks to new technology like the Swiss Free Electron Laser, we’ve been able to answer these questions about DNA repair by directly “seeing” them with X-rays, giving us a view into how life is able to survive and thrive under the sun.