⏱️ Time for a statistical crystallography

Published:

We’ve learned a lot about static structure from single, frozen crystals. But could we learn about dynamics by studying thousands of cryogenic crystals, using just standard data collection techniques at a synchrotron?

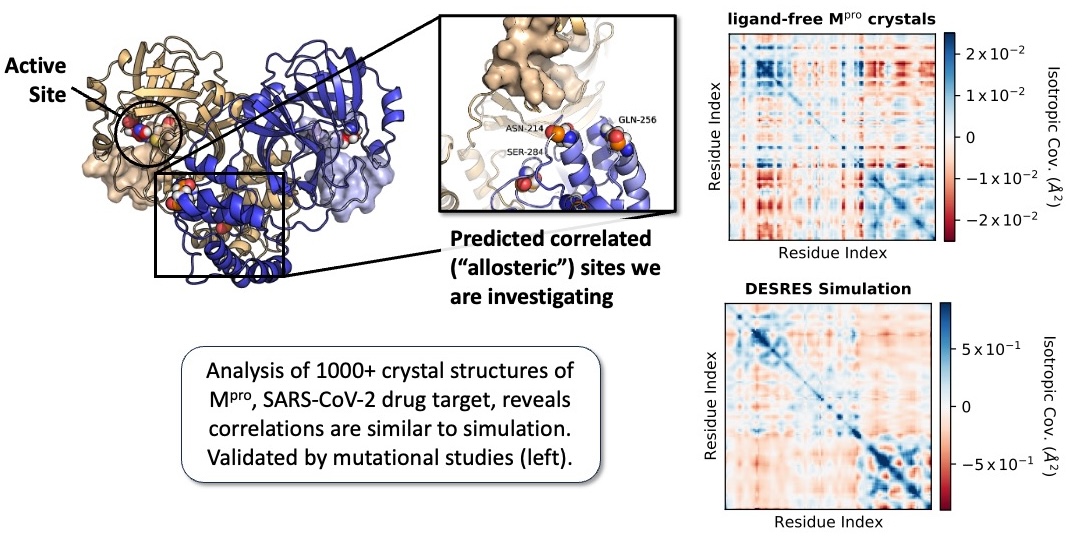

We’ve been studying the main protease (Mpro) from SARS-CoV-2, an enzyme that activates via homodimerization. We asked a simple question: can we use crystal-to-crystal variation, and a huge dataset, to learn about how structure changes upon dimerization? That is: to learn about how protein dynamics generate function?

Our study is based on a trove of thousands of crystal structures of Mpro, a dataset 100x larger than is typical, that we produced during a COVID ligand screening campaign. Even though all samples were nominally prepared in the same way there is structural variability in the dataset. We hypothesized that this distribution of structures might reflect the native dynamics of the protein in solution – indeed, it qualitatively matches MD simulations.

By computing residue-level covariance across this ensemble, we were able to identify residues whose motions are statistically coupled to the active site, including some in the distant dimerization domain. As Mpro’s activity is regulated by dimerization, we used our ensemble to predict how structural correlations between the enzyme’s active site and dimer interface modulate function.

We then mutated three of these residues and found striking effects:

- One mutation (N214A) significantly weakened dimerization and crippled catalytic turnover.

- A second (Q256A) modestly reduced both binding affinity and activity.

- A third (S284A) had no measurable effect, but follow up crystallography work shows that the mutation does not significantly perturb the protein structure.

Follow-up structural and biophysical data helped rationalize the outcomes: in the case of N214A, for example, we observed disruption of an H-bond network that normally stabilizes the oxyanion hole during catalysis.

What’s most exciting is that these results were measured experimentally and not inferred from MD simulations or mutagenesis. Instead, we leveraged structural variation induced by mild, uncontrolled perturbations (like air exposure during crystal mounting).

We call this approach statistical crystallography and propose a “perturbative crystallographic conjecture”: that mild perturbations to crystals can be used to reveal functionally relevant motions. In this case, we used it to identify an allosteric network that couples Mpro dimerization to catalytic activity.

While important in its own right, the Mpro system is above all a proof of principle. We conjecture that the analysis of many crystals will be a general way to determine the dynamics of protein native states. While a dataset of thousands of crystals is extreme today, high-throughput crystallography is coming tomorrow: for example, the X-Chem beamline at Diamond Light Source is aiming to collect up to 5,000 datasets/day after their upgrade later this decade. Those resources are being martialed primarily for ligand screening – but our work demonstrates an entirely new and equally exciting application the community could and should prepare for.

For the full story, read our preprint.